I've had a lot of fights where I was the only participant. Thankfully, they've all happened in my head and not in a scene out of Fight Club. The animosity of these intense moments is rarely directed at myself. Whichever poor soul I'm dwelling on isn't actually present, I've conjured him up with my overactive imagination. Sometimes I'm steeped in a moment where I felt slighted. Other times I'm envisioning future disagreements that I imagine are heading towards me. Sometimes I'm simply shadowboxing, beating up some straw-man standing in for a viewpoint I find hard to tolerate. Fantasizing of this type is anti-Stoic. It's the willful practice of negative emotions and misanthropic thoughts! It's as far afield as one can get from the present-focused attention that Stoicism demands. So what to do?

Stop fantasizing! Cut the strings of desire that keep you dancing like a puppet. Draw a circle around the present moment. Recognize what is happening either to you or to someone else. Dissect everything into its causal and material elements. Ponder your final hour. Leave the wrong with the person who did it.

-Marcus Aurelius, 7:29 (The Emperor's Handbook)

Aurelius' first line has also been translated, "wipe out the imagination," but I believe "fantasizing" better captures his meaning. The Emperor doesn't want to waste his life working himself up over the unreal. To combat his wandering thoughts, he reminds himself of five stoic mental practices:

- Attend to the present moment

- Focus on what affects people here and now

- Break things down until they are understandable and manageable

- Remember that life is short

- "Leave the wrong with the person who did it."

My internal monologue, like Aurelius', is often far removed from the here and now. In contrast, the stoic mind is rooted in the present, because the present moment is the only time in which a Stoic can exercise control. Seneca put it this way, "These two things must be cut away: fear of the future, and the memory of past sufferings. The latter no longer concern me, and the future does not concern me yet." We regain our footing by attending to what is happening now.

When Stoics decide what to do in the present moment, our thoughts should be concerned with the people we can help. As Aurelius reminds himself in Chapter 9 of his meditations, "Passivity with regard to the events brought about by an exterior cause. Justice in the actions brought about by the cause that is within you. In other words, let your impulse to act and your action have as their goal the service of the human community, because that, for you, is in conformity with your nature." Chances are, if I were to pay attention to what's happening to the people around me, I'd find something better to do than daydream.

The Emperor's self-admonition to, "dissect everything into its causal and material elements," is a bit more esoteric. Donald Robertson, in his new book Stoicism and the Art of Happiness, explains it like this:

The Stoic strategy of seeing the present moment in isolation...appears to be closely related to another technique...called ‘physical definition’. This involves cultivating the calm detachment of a natural philosopher or scientist. We are to practice describing an object or event purely in terms of its objective qualities, stripped of any emotive rhetoric or value judgements, to arrive at an ‘objective representation’ (phantasia katalêptikê)... However, especially in the writings of Marcus Aurelius, this may also involve a kind of ‘method of division’, in which the event becomes broken down through analysis, calmly dissected into its individual components or aspects.

By breaking things down into smaller parts, Aurelius seeks to demystify the happenings in life. For instance, to get past lust he memorably describes sex as, "friction of the genitals with the excretion of mucus in spasms." Now that's a mood killer. Speaking of killer, on to our impending doom!

"Ponder your final hour," is a Stoic version of YOLO. Life is short. If we want life to have meaning, we should build that meaning in the here and now, not in our imaginations. Unfortunately death is a taboo subject in western society so it would take too long to make a case for the positive aspects of dwelling on mortality. However, check out Here Is Today, if you want to meditate on how the lifespan of the universe makes us all look like mayflies. I know that if I really took the shortness of life to heart, I'd stop wasting thoughts on some guy that cut me off an hour ago.

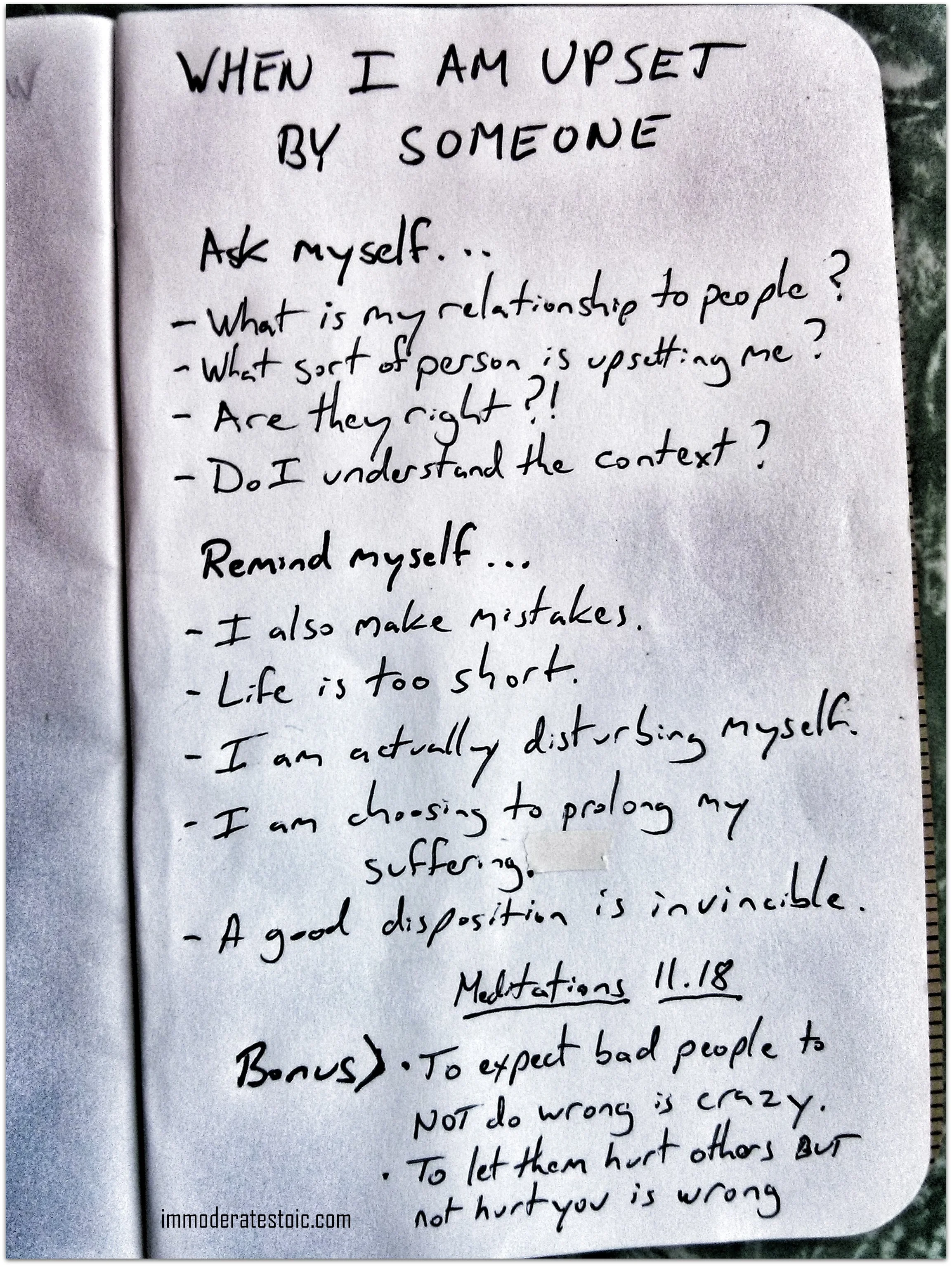

Marcus Aurelius' final advice to himself is, "leave the wrong with the person who did it." Why burden ourselves with someone else's moral failings? Don't we have enough of our own problems to worry about? Of course, this doesn't mean we allow people to do evil things. Stoic actions are for the good of humankind, after all. But we should not burn with indignation at another person's actions. Instead, we should make certain that our own thoughts and actions are good, since that's all that we truly control.

Each of these five techniques rely on a core stoic skill, the ability to pay attention. Stoicism can only be practiced with an attentive mind.

Attention is the fundamental Stoic spiritual attitude. It is a continuous vigilance and presence of mind, self-consciousness which never sleeps, and a constant tension of the spirit. Thanks to this attitude, the philosopher is fully aware of what he does at each instant, and he wills his actions fully.

-Pierre Hadot

There's no such thing as unconscious Stoicism. Attention is fundamental. When my mind is wandering, I'm losing out. I'm denying myself the pleasure of living a life of impact and meaning. In those moments I am not stoic. Thankfully, a quick reminder of what is stoic, and the will to put that into practice is all it takes to get back on the path. It's simple, but strenuous. Hadot's, "constant tension of the spirit," requires dedication. Thankfully, the long gone Stoics of the past left me a few Cliff Notes to help out along the way. I hope your internal monologue is less infernal than mine, but if not, I hope these techniques are as helpful to you as they are to me.