Commit these nine observations to memory; accept them as gifts from the Muses; and while you still have life, begin to live...

The Emperor's Handbook 11:18

I keep track of my thoughts about Stoicism in a notebook that I try to keep near me. Most of its pages are incoherent; containing scattered musings from recent readings or reminders to revisit some chapter or other when I get the chance. From time to time, however, a Stoic author lays out an idea in such a succinct manner that the notes I create from it are practical. Book 11, Chapter 18 of Aurelius' Meditations is just such a usable bit of writing.

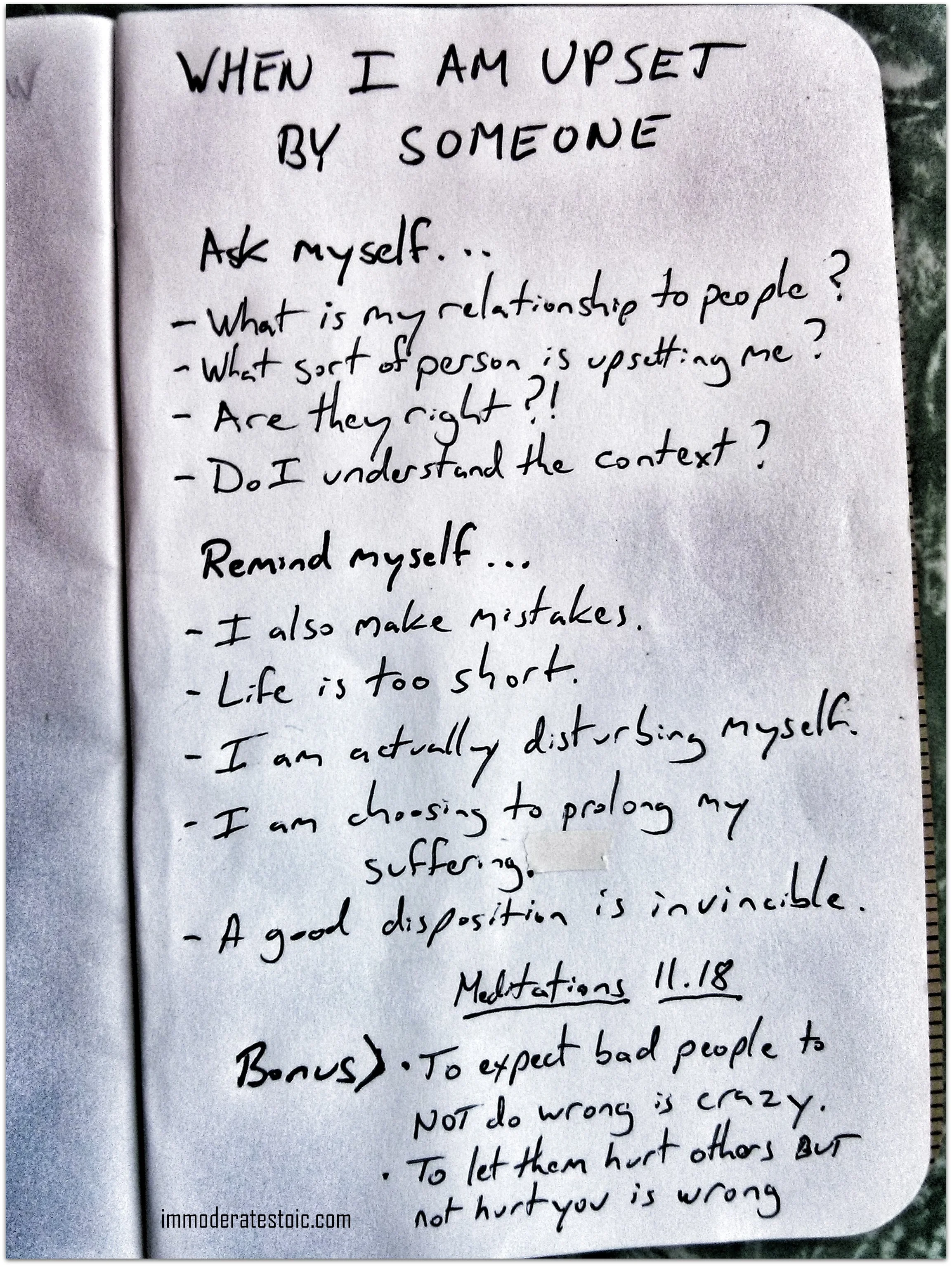

A page from Matt Van Natta's notebook. Points derived from Marcus Aurelius' Meditations, 11.18.

These four questions and five reminders are a certain means of regaining a Stoic mindset if we are set off balance by the day's social interactions. Of course, in order for them to be effective, we need a clear understanding of the worldview that informs the exercise.

- What is my relationship to others?

Marcus Aurelius' short answer is, "we are made for each other." The Stoic view is that our highest purpose is fulfilled by serving others. We should seek to do right by everyone we meet, even if they are not returning the favor.

- What sort of person is upsetting me?

Evaluate the person you're dealing with. Aurelius breaks this down into sub-questions: What actions do their opinions compel them to perform and to what extent are their actions motivated by pride? Stoics never expect people with bad information to make good decisions.

- Are they right?!

Check yourself. You could be the one that's in the wrong. Never forget that you are fallible.

- Do I understand the context?

Aurelius reminds us that, "Many things are done for reasons that are not apparent. A man must know a great deal before condemning another person's behavior." Looking back to the question "are they right," the Stoic default position is, "I don't know." It's difficult enough to keep ourselves on a consistent path of virtue, why waste time guessing where someone else is at?

- I also make mistakes.

If we expect any grace from others when we stumble, shouldn't we be willing to give the same to them?

- Life is too short.

"Think...how soon you and your vexations will be laid in the grave." Aurelius didn't want to spend his time angry and impatient when he could, instead, pursue happiness. It's sound advice.

- I am actually disturbing myself.

Stoics hold ourselves responsible for our emotions. As Epictetus put it, "it is not circumstances themselves that trouble people, but their judgement about those circumstances." It's important to realize that we can't control how others act, but we can choose how we will respond. Aurelius reminds himself that, "it isn't what others do that troubles you. That is on their own consciences. You are bothered by your opinions of what they do. Rid yourself of those opinions and stop assuming the worst - then your troubles will go away. How do you get rid of your opinions? By reminding yourself that you aren't disgraced by what others do."

- I am choosing to prolong my suffering.

"Our rage and lamentations do us more harm than whatever caused our anger and grief in the first place." Again Aurelius lays bare the ridiculousness of fuming about another person's actions.

- A good disposition is invincible.

"What can the most insolent man do if you remain relentlessly kind and, given the opportunity, counsel him calmly and gently even while he's trying to harm you?" I sort of love the term "relentlessly kind." If we succeed at keeping a Stoic mindset during every social interaction, then we will genuinely value each and every person we meet. This would have to be unnerving! I'm picturing a salesperson who is speaking nicely but seems to have spite behind their eyes. However, Aurelius isn't counseling a faux friendliness. In fact, he continues, "Let their be nothing ironic or scolding in your tone, but speak with true affection and with no residue of resentment in your heart. Don't lecture him. Don't embarrass him in front of others. But address him privately even if others are present."

We're not going to run out of situations that make these points useful. Emperor Aurelius advised himself to memorize them. You may want to as well. Or, like me, you might choose to carry a reminder with you. I know that when I turn to the nine points of Meditations 11:18, I find it impossible to continue stoking the anger that's in me. I'm reminded of the practical outcomes that are expected from a lived Stoic philosophy. I realize that if I truly believe that all people have value and that we are meant to work together, I can not act against that truth and consider myself reasonable. I suspect that taking a page from Aurelius will work as well for you.

All Aurelius quotes from The Emperor's Handbook, a new translation of the Meditations.